This article was published by LLOYDS LIST recently.

It does raise some serious issues such as training, multi national crews, the design and standardisation of bridges and bridge equipment, the bridge management team which could include some who may have little knowledge of shiphandling and the use of a helmsman when modern auto pilots and ECDIS should replace this out of date and antique method of steering a modern ship.

How did a modern cruise ship end up being without command for about five minutes as it steamed straight towards well known and charted rocks one dark evening?

And when those rocks loomed large in the darkness, how was it that the urgent commands of its master were being challenged and then allegedly misunderstood by a helmsman who could not fully understand English, the language of the sea, nor Italian, the native language of the ships officers?

The results were disastrous and led directly to the deaths of 32 passengers and crew of Costa Concordia on the evening of Friday 13 January 2012 off the Italian island of Giglio.

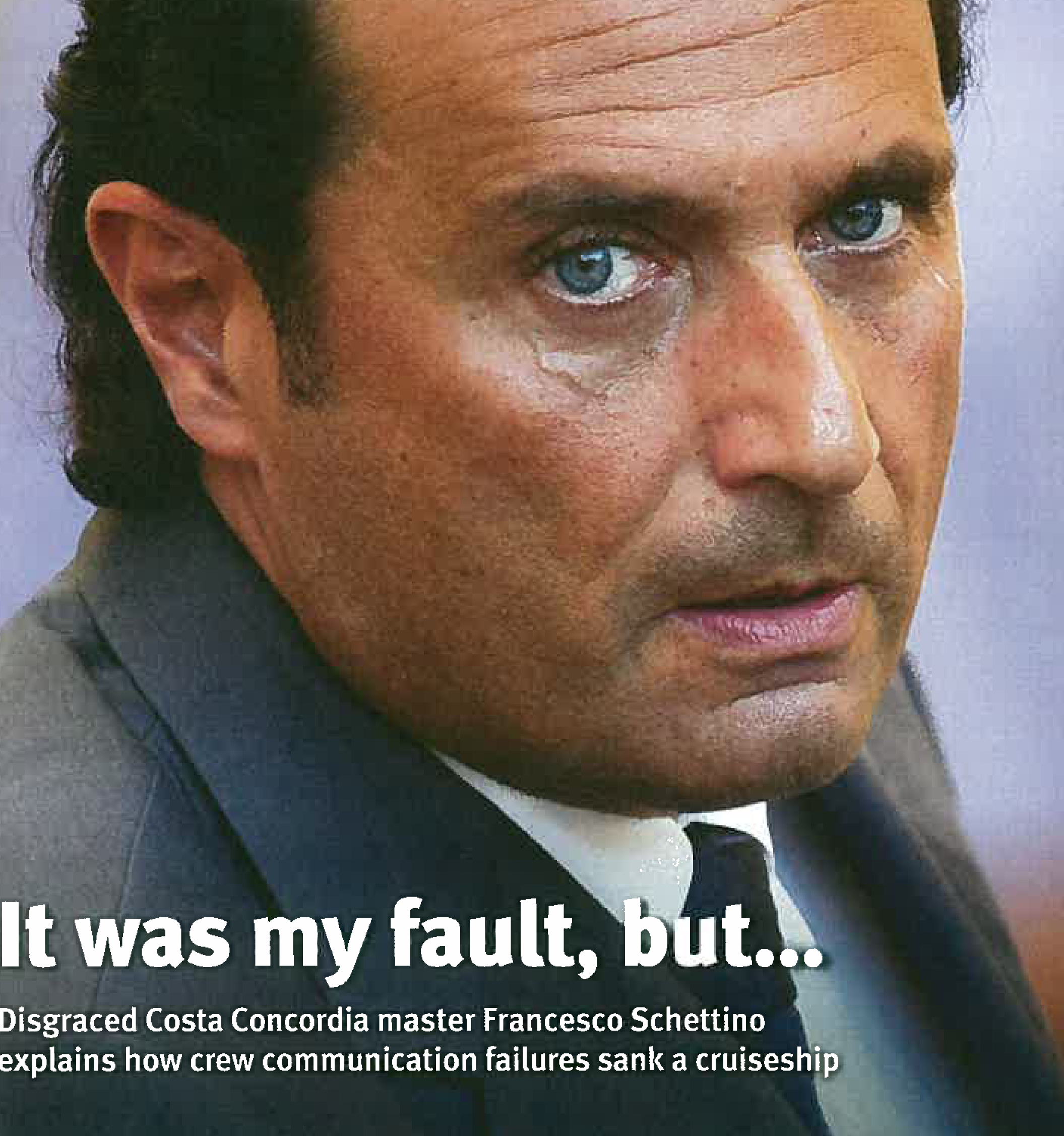

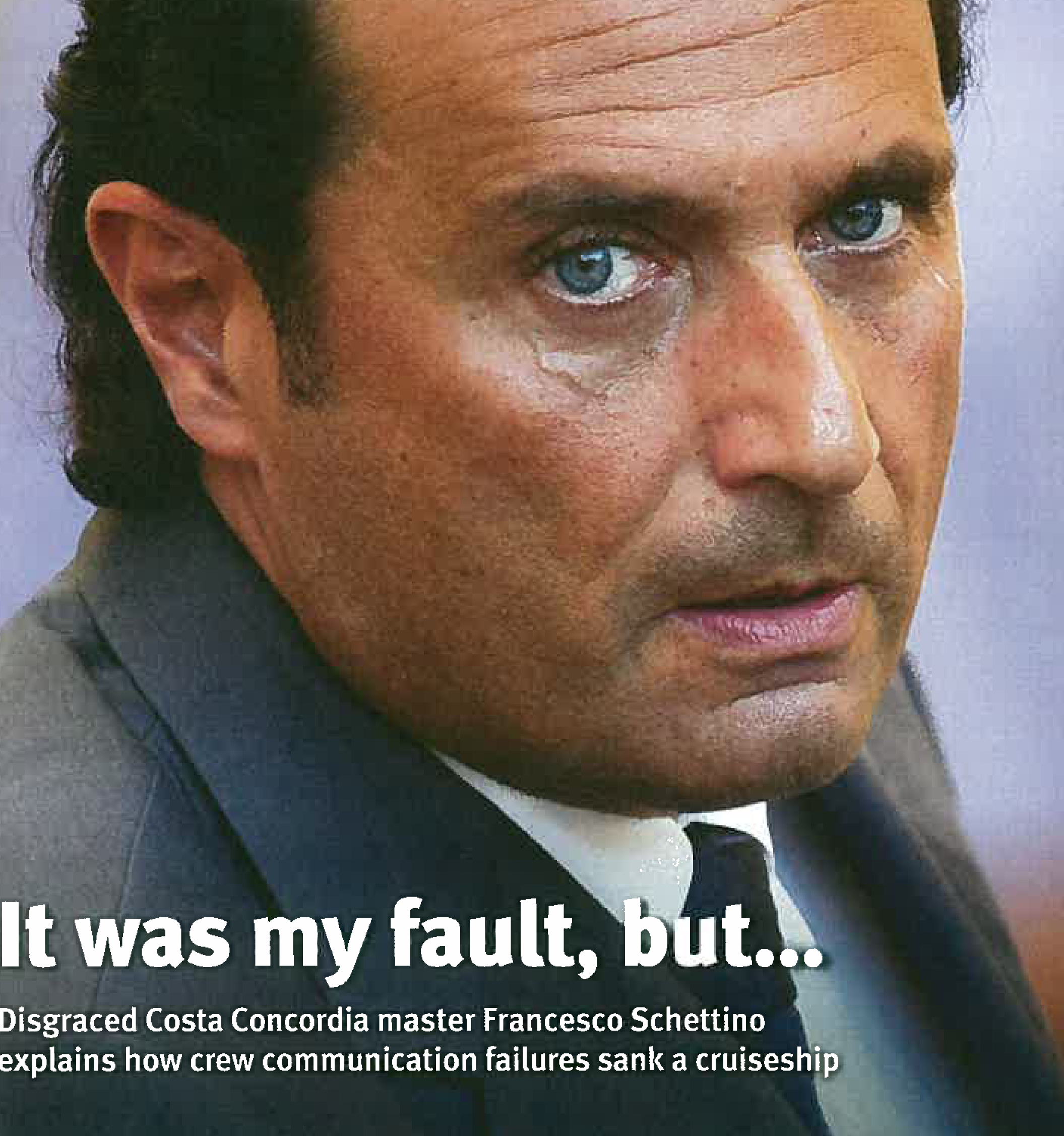

The blame has fallen squarely on the ship’s master, but Francesco Schettino is now fighting back.

The 54-year-old disgraced mariner now faces a 16-year prison sentence for the manslaughter of the 32 souls lost. But whether or not one believes he was an arrogant, showboating captain, there are some serious questions about the vessel’s bridge management and navigational procedures that raise worrying questions across the shipping industry. These are questions that have been asked about other disasters in the recent past and have yet to be fully answered.

Schettino describes his drawn-out and public trial, which ended this summer, as a travesty. Not because he was found guilty – he says he accepts his responsibility for the casualty and its consequences as a ship’s master – but because the real details behind the cause of the accident were too technical for the court to understand.

“All the previous lawyers were not able to present the nautical issues that led to the accident,” he tells Lloyd’s List during a late night telephone conversation, following days talking to his lawyer as he prepares to appeal.

“I do not blame people, but this is a nautical issue, and it is not easy for a civil judge to absorb and understand,” he says. He adds that neither the defence nor the prosecution had experts in maritime technology, ship construction, bridge manning and navigation.

The persecution of Schettino in the Italian and international press has been relentless and his attempts to explain the events that fateful evening that led to disaster and death have largely been described as a cowardly attempt to shift blame and exonerate himself.

But is there something in what he is trying to say? The original court and the international press as a result, failed to take on board industry wide questions and issues facing electronic chart usage and the application of the international safety management code.

However, while Schettino wants to put his story forward without the clamour for blood, his version is already contradictory to those of the other members of the navigation team that were on the bridge that night all of whom have been able to avoid prison sentences by agreeing to plea bargains. Schettino’s request for a plea bargain were rejected.

Costa Crociere, the Carnival Corporation shipowner, also avoided being put in the dock by agreeing to pay a fine, thus leaving Schettino out on his own. This is something that Schettino says he understands, calling it “commercial tactics” and adding that he is not looking to attack his former employer. But he also points to the fact that it was not his decision to employ the young bridge officers that formed his navigation team nor to select the bridge equipment that they and he used.

It was his job, though, to say how the equipment should be used.

However, what is of interest and will be a wake-up call for many in the shipping industry, is the growing support Schettino has, and the fundamental questions that are being asked about modern bridge practices.

These bridge and navigation issues that Schettino is raising in his defence should be listened to, according to safety experts such as Arne Sagen, the Norwegian accident inspector from the Skagerrak Foundation. In the past, Mr Sagen has been vociferous about how lax management standards and modern technology are becoming a dangerous mix. Similarly, a report by Antonio Di Lieto at the Australian Maritime College at the University of Tasmania also highlights institutional failings that led to the grounding of Costa Concordia.

While it shows Schettino has some blame to shoulder, it supports the view that he should not be alone. In short, how was it that a fairly new vessel with a supposedly competent bridge team and the latest electronic navigational equipment found itself out of position, without the bridge team realising?

Why did the team not have the procedures to clearly determine, when the master came onto the bridge, whether he had taken the navigation conn? And why did the company allegedly have an Indonesian crew member/helmsman who could speak neither English nor Italian sufficiently to understand rudder commands?

In Schettino’s own words: What happened before the ship hit the rocks?

Schettino wants his version of the events leading up to the grounding of Costa Concordia heard without the media continually baying for blood. He has written a book, in Italian, to try to 8et that message across. He insists he is not a “tiger captain”, one who shouts orders and does not allow for feedback. He also insists that when he went to the bridge that night, he was not in command of the bridge team, but had only gone up to perform the salute as the vessel passed the island of Giglio, which it had done before, and for which he has been accused of “showboating”.

When asked why none of the officers on watch asked him to take command of the bridge when there was a perceived problem, Schettino is unable to answer. “They were not willing to give me bad news,” he says, adding that as he was on the bridge on a social errand, he left the bridge team to do the navigation thinking that everything was okay. He was, he says, not in charge of the navigation until he clearly said he was. However there are reports that the senior officer on the bridge, who was in charge of the bridge team, thought he was.

This means, and Schettino admits this, there is a three to five-minute window when there was no one in command of navigation and Costa Concordia was continuing its rapid approach to the rocks at Isle le Scole.

“It was my fault. I went to the bridge to perform the salute. I never expected to take the conn. According to the passage plan we should have been a half nautical mile off the rocks. l can’t blame, I take responsibility, but I was leading a bridge team that was not properly trained.”

And this is a common theme when Schettino speaks. He takes responsibility, but he also believes the officers were not familiar with the ecdis. ECDIS, the electronic chart display and information system, is a mandatory piece of technology on all passenger ships now, and slowly being rolled out across the world’s merchant fleet. Soon all ships will have at least one system on board, and owners and managers will need to ensure that navigation officers are properly trained in their use.

There is well known criticism about the range of different ecdis systems, with different features, hence the requirement for proper training.

Schettino says the bridge officers were expected to have on board training on the ecdis, rather than shore based training. However, there is also the accusation that the ecdis on Costa Concordia should not have been used as an ecdis, as it did not have the right type of charts installed.

Simply put, an ecdis is an ecdis if it has what is called a “vector” electronic chart that has sets of data that allows for more detailed interrogation by an officer, The “raster” chart that the Costa Concordia System is reported to have had could not be used as a primary source of navigation, and strictly speaking was not to be called an ecdis.

Yet in Schettino’s own words he had let the bridge team repeatedly use the electronic chart system “l often said to them the other navigation officers that I would need to get the bosun to repaint the deck in front of the screens and the rudder [autopilot] where their feet had worn the paint away ”

Schettino admits that while he had not taken control of the navigation when he entered the bridge, he had asked the officer on watch what actions he was taking, particularly in relation to using manual steering and altering course at a given waypoint. “It was a misunderstanding,” he concedes. He expected the bridge team to tell him more than they did. “The question is, was this guy thinking I took the con when I entered the bridge?” asks Schettino. “Why were they not screaming at me that something was wrong? Why were these officers not able to recognise when the captain is approaching the point of no return?”

The assumption is that either the bridge team did not know how critical the situation was, or were afraid.

“There was no information given to me. The absence of information made me think that everything was fine. But this soon changed” he says, as he became aware of the situation, and took the con. Schettino says that whenever he took the con of Costa Concordia when performing manoeuvres he would order two steering pumps to be used, rather than the single pump, With two Pumps the rudder, and therefore the ship’s heading, responds more quickly to a helm command.

“l was forced to go hard to starboard, but I was asked Why are you changing course, we are passing clear?” ‘”It would have been scary to see [the rocks] if it was daylight, I blame the fact that the officers could not differentiate between the real world and that of the ecdis and the rudder. After l was ordering angles of starboard rudder l was forced to go hard to port,” says Schettino describing how the officer on watch did not understand why the centre of the ship’s turning circle as it began to move to starboard was towards the forward lifeboats, according to Schettino.

This means as the rudders turned the bow to starboard and the vessel bodily moved that direction, the vessel’s stern swung to port and towards the rocks. Schettino’s sudden and dramatic hard turn to port with the ships rudder was an attempt to minimise the damage by trying to swing the stern away from the rocks.

Schettino says that fellow officer who did not understand why he had made the command to turn to port and had counter ordered to go further to starboard.

The Indonesian helmsman could not fully understand English or Italian and to whom a junior officer on chart plotting duties was forced to stop what she was doing and render assistance.

There are even reports that the helmsman, who Schettino says has now vanished without trace had even been turning the in the opposite way to the commands he was given.

The rest of the night following the strike, the heeling and the manoeuvring to get the vessel onto the coast of Giglio and the frantic, fraught and frightful evacuation are now ingrained in shipping history.

This casualty has already led to international discussions about the way cruise ships are built, their survivability (safe return to port) and the evacuation of passengers. But there are those questions over navigation, ecdis and the lSM Code.

According to accident investigator and longtime campaigner for safer shipping Arne Sagen, the grounding of Costa Concordia joins a growing series of typical ecdis assisted accident, some of which have been fatal. He cites cases such as a Color Line grounding in 1994 and the Rocknes disaster in 2004, both in Norway, where the combined use of paper and electronic charts was instrumental to the accidents.

It looks as if in such cases, with lack of approved electronic charts, it is quite common to navigate by the combination of paper charts and the electronic navigational system, where the paper chart has priority. Mr Sagen’s thinking is to question if the mismatch of information and navigation between paper charts and electronic charts is still leading to confusion.

It is worth noting, he says, that the International Chamber of Shipping’s bridge procedures guide advises ‘planning within any one phase of the voyage should be undertaken using either all electronic or ail paper charts rather than a mix of chart types.

Mr Sagen’s appraisal of navigational procedures is supported by research from Capt Di Lieto, a bridge simulator expert and PhD candidate at the Australian Maritime College at the University of Tasmania. Who addressed the accident in a paper ‘Anatomy of An Organisational Accident’.

Capt Di Lieto’s paper lists a number of active errors, some made by Schettino, some by the bridge team overall, and some by the company, that came together to create the conditions for the accident.

These errors range from changing the route plan without proper consultation with other bodies outside the vessel; a failure to draw the new route on the paper chart or at least not on one of suitable scale for such navigation; a failure by the officer on watch to monitor the route; and the language barrier with the seafarer who assumed the helm. To address the risk of crews not knowing an ecdis, there must be more consultation between crews and the purchasing and technical departments ahead of a system being installed, says Mr Sagen.

There has been some key work to upgrade ecdis systems, including an “S-mode” proposal by the Nautical Institute back in 2008. Schettino also complains that other navigational officers used Costa Concordia. Electronic chart display “like a video game” and he had instructions to have it set in a particular way when he was due to come up to the bridge for port and other manoeuvres.

Mr Sagen wants the use of ecdis to be fully controlled. “We will go even further and claim that there shoutd also be an organised liaison between the shipping company and the national and hydrographical institutions combined with national restrictions for the use of ecdis in certain waters,” he suggests.

The International Safety Management Code was born out of the Herald of Free Enterprise disaster in 1987 when the Townsend Thoresen ro-pax ferry capsized as it left Zeebrugge, leading to the deaths of 193 passengers and crew.

The vessel’s bow doors had been left open due to a crew member being asleep rather than on duty. The accident investigation at the time found there were institutional errors within the company that led to lax safety procedures.

It is worth noting that a judge assessing the case in 2000 decided not to imprison the captain and crew, who were found to be at fault, opting to ban them from working at sea for a period. He recognised that the fault was as much with the ship owner as on board the ship. His decision is in stark contrast to events in Italy.

The ensuing ISM code was a way for the international regulators to address this safety issue by forcing ship owners to take more accountability and responsibility. The detail of a vessel’s ISM code are, however, compiled by the ship owner, and audited by a third party, usually a class society. It is based on the concept of risk assessment and improvement particularly in relation to the skills and competence of employees.

The essence of the code and how it should work, is that it reties on a proactive approach from a ship owner, rather than the owner applying lip service to it just to remain in compliance and therefore have a vessel able to trade.

As it provides a paper trail in accountability the ISM code can be used to identify safety loopholes. However, this paperwork of accountability can then also be used to find a fault, and then apportion blame, which according to experts is not what it is set up to do.

Under the ISM Code, a shipping company has the responsibility to ensure proper manning, training, even before navigators are placed on the bridge and told to use the equipment for the first time. Mr Sagen questions if this is robust enough, given the incidents that can happen.

He also questions ISM procedures that seem good on paper, but, in his mind, prove to be useless when it comes to an emergency. He highlights a vessel’s turning circle in an emergency. When the bridge team is shifting to manual steering by helmsman, a possible critical navigation may become even more critical. ln manual steering mode the most common rudder control will be done without proper situational awareness. This means that a vessel’s turning circle in relation to the rudder position and the speed is not indicated to the bridge. Mr Sagen argues that an officer in charge is not able to predict the optimal rudder angle when steering is manual, as he does when the vessel is under the automated control of ecdis and an autopilot. And this could lead to disaster.